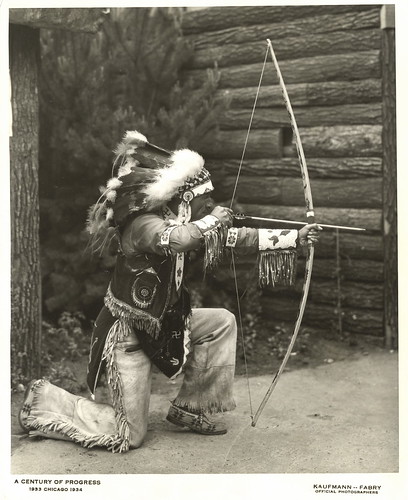

[American Indian demonstrating the use of a bow and arrow], originally uploaded by UIC Digital Collections.

To take an animal with bow and arrow a hunter has to penetrate a defense system of sight, hearing, smell and instinct perfected over thousands of years of evolution. A lofty challenge. He has to get in tight - 30 yards is the maximum for most. Creeping within range of a mule deer or sheep or bear seems an impossible task. One on one. Only those able to hunt stealthily have a chance. Bow hunting is a solitary pursuit where a hunter is absorbed by the subtleties of nature. Undetected. Holding motionless in a stand, waiting to see if scouting has paid off, controlling nerves when a whitetail materializes as if by magic and moves into range ... the slightest error or squeak or breath and it will all be over. Or not. The satisfaction of taking big game with bow and arrow cannot be described, only felt by those who have earned the feeling. Bowhunting is the chance to gain a oneness with the outdoors, to hear elk bugling or watch deer rutting, to see and smell autumn at its peak, to have a chickadee land on your nocked arrow. It's a season extender, a way to get out and hunt again with few other hunters in the woods. Bowhunting is tradition. It takes practice and dedication. Here is a look at the latest.

compounds vs. traditional

Chuck Adams was the first person to take all 27 North American big-game animals - the Super Slam - with a bow. He has written nine books on archery and bowhunting. E. Donnall Thomas Jr. has used traditional tackle exclusively for the last 15 years. He is editor of Traditional Bowhunter Magazine and author of Longbows In The Far North.

compounds

I grew up hunting deer and bears with recurve bows. But compound bows are clearly better for taking game. Here's why: A compound's principal advantage is dramatic weight reduction at full draw. For example, a 5 5 -pound deer bow exerts only 22 to 27 pounds of pressure on your fingers and shooting muscles as you aim and release the bowstring. A 55-pound curve bow or longbow exerts a full 55 pounds at full draw. In my experience, a modern bowhunter with average time for target practice will shoot significantly better with a compound bow. Less muscle strain means steadier aiming at targets and animals.

One of a compound bow's chief attributes is game-harvesting power. A modern, cam-operated compound produces up to 30 percent more kinetic energy than a recurve bow of the same draw weight. This energy drives a broadhead deeper through vital tissue and shatters bone along the arrow's path. When used with properly chosen, relatively lightweight arrows, compound bow power also yields flatter trajectory for surer hits at unknown shooting distances.

Without exception, a compound shooter is more accurate than a recurve or longbow shooter with comparable target and hunting experience. Non-compound bows require long hours of practice to keep shooting muscles in shape and unusually developed hand/eye coordination to place arrows on target. Learning to shoot a recurve or longbow demands hard work and dedication. This might be fine for a few traditional experts, but most modern bowhunters have neither the time nor the inclination to become truly proficient with a noncompound bow.

A majority of stick-bow archers aim without the benefit of bowsights. By comparison, a compound bow is ideal for deliberate draw-and-aim sight shooting. If you perfect your proficiency to judge distance by eye, you will greatly enhance your ability to hit where you aim.

Some archers sneer at compound bows as ugly, non-dependable shooting implements. A well-made recurve or longbow is certainly lovely to behold. But data from major archery companies prove that compounds and non-compounds are statistically equal in terms of warranty repair. A modern compound bow is no more likely to malfunction than a modern recurve bow.

Recurve bows and longbows can be deadly in expert hands, but they take year-round dedication and practice to master. Hunting is serious business, and I believe that most bowhunters are better served by compound bows.

traditional

I like my bamboo fly rod. I like the 12-gauge over/under that I've carried across the prairie for two dozen years. But I love my longbow, the 66-inch masterpiece in Osage orange and black locust with which I have hunted from one end of the world to the other.

Before explaining the subjective elements of traditional archery's appeal, I would emphasize that there are practical reasons why many bowhunters regard longbows and recurves as ideal for hunting. They are easy to set up and maintain. The absence of complex parts means that there is little to go wrong in the field, and their light weight makes them a pleasure to carry. Finally, many experienced hunters regard the instinctive shooting style as the most effective under actual hunting conditions, when sights, range finders and releases can hinder as much as they help.

On the other hand, there is little doubt the average archer can shoot a compound more accurately than a traditional bow, especially over distance. But the architects of bowhunting's modern revival - especially Saxton Pope and Art Young - conceived their new passion in response to technology's impact upon the hunt. They became advocates of the bow because archery enhanced their appreciation of the natural world and the development of their hunting skills by virtue of its limitations.

For those who share these convictions, the essential step in the commitment to bowhunting becomes the decision to voluntarily limit one's means of take. I can trace all of the best experiences in my own bowhunting career back to these principles: The incredible challenge of operating at close range while hunting large, wary, and sometimes dangerous animals; the satisfaction of a perfect arrow delivered by a simple bow; the knowledge that success, when it comes, is the product of skill and persistence (and sometimes more than a little luck) rather than something that came out of a catalog with a serial number stamped on its side.

Fascination with the elegance and grace of traditional bows is common to cultures worldwide. Such bows' physics are marvelously economical: They give back precisely what you invest in them. They offer an intimacy between archer and equipment that no compound can ever provide, no matter how flat its trajectory or mind-boggling the numbers on the chronograph. Finally, each one of them is unique, a product of distinctive woods and an expression of the bowyer's art.

This is not to suggest that one group of bowhunters is morally superior to any other. And traditional tackle is not the right choice for everyone. But anyone willing to examine bowhunting's values should ask whether technology can ever provide true solutions to challenges in the field. For those who think the matter through, a longbow or recurve may be the passport to a brave new world of challenge and satisfaction.

the carbon craze

The first time I toyed with carbon arrow shafts, I wasn't impressed. The point adapter cemented to the outside of the shaft looked goofy compared with the insert that glues neatly inside aluminum arrows. And a fletch job was a pain with so little surface area on the ultra-thin shafts. But after shooting and testing these shafts extensively, I discovered that thin is in for hunting arrows, and carbon arrows look like the wave of the future in bowhunting.

If you're among the 12 to 15 percent of archers who shoot carbon arrows, you're pointed in the right direction. Many industry experts predict that half of the nation's bowhunters will shoot carbon by the turn of the century (Olympic archers already shoot carbon or carbon/aluminum composite). This is remarkable considering that carbon shafts first appeared in 1988.

The carbon craze is more than a fad for a quiver full of reasons. Topping the list is arrow speed. Carbon shafts are proportionately fighter than other materials, enabling an increase of velocity by 20 percent or more without sacrificing proper arrow spine. Increased velocity means flatter trajectory, a potent antidote for faulty range estimation. To prove that point, I recently shot two identically equipped arrows - Easton 2512 aluminums and Beman 60/80 carbons - out of the same compound bow. At 45 yards, the carbon's point-of-impact was 21 inches higher when shot at the same bull's-eye.

Next is penetration. A carbon arrow makes up for its slight loss in kinetic energy (approximately 3 percent, due to it being lighter than aluminum) in several ways. First is that carbon's thinner diameter reduces surface drag at impact. Once the broadhead - with its ferrule adapter being wider than the arrow shaft - blasts through, the shaft slides behind with little drag. The opposite is true with wider aluminum arrows in which the broadhead is thinner than the shaft. Although stretching of cut muscle tissue and "lubricity" temper this somewhat, blowing through bone and cartilage is easier with carbon, all factors being equal.

It takes about six pounds of pressure to permanently bend aluminum, 29 to 32 pounds to break carbon. This reduces paradox, or arrow flex, in flight. Carbon bends less so it recovers more quickly at release, making shafts easier to tune to your bow. One shaft typically accommodates a surprisingly wide range of bows. And because carbon is either straight or broken (it can splinter and should be inspected regularly), you won't experience unexpected erratic arrow flight from a bent arrow.

Carbon's future is wide open. If carbon does to bowhunting what graphite did to fishing, as some claim it will, you'd be crazy to ignore the carbon craze.

the cutting edge

Accuracy. Sharpness. Cutting width. Durability. Penetration. Confidence. No single broadhead offers the best of all characteristics, and some virtues have drawbacks. Here is a guide to help you choose the head that's best for you.

Accuracy: This sounds elementary but is not. A heavy two-bladed head win fly went for some shooters and a super-fight four-blader will hit bull's-eyes for others-it depends on individual bow setups and shooting styles. To get a particular head to fly well can take time and effort. You may have to tune your bow or change your arrows to get a specific broadhead to fly well, or you may have to test several heads before you find one that's best for your style. The bottom line is this: A broadhead that does not group consistently in practice should not be used in the field.

Sharpness: Razor-sharp blades are critical. You can sharpen your own solid steel heads or buy heads that come scalpel-sharp right out of the package. The trade-off is that packaged replaceable heads don't have the bone-breaking ruggedness of self-sharpened solid steel heads.

Cutting width: In this category, there is no hallowed ground. A wider head or one with multiple blades can catch the edge of a vital organ on a marginally placed shot. The trade-off is that wider heads are more prone to wind-planing, and their extra weight can create rainbow trajectories. Similarly heads, with four or more blades may retard penetration and fly erratically for some shooters. Two-bladed heads generally slice deeper than others but sacrifice total cutting area.

A compromise can be found in the new wave of heads that expand on impact, such as the Vortex. They're accurate and forgiving, and they offer some eye-opening widths. The question is, will they provide the necessary confidence when that big buck walks into range?

Penetration: Although most experts agree that cutting edge, razor-tip broadheads (of the Zwickey type) provide the best penetration, chisel-tip heads have blades that are easier to keep sharp (you simply replace them) and provide more than adequate penetration with properly placed shots.

Confidence: When all other factors are boiled down, consider this: After you find a broadhead that shoots well from your bow and that meets the requirements for your type of hunting, stick with it and get to know it. Don't always think that there's a better head out there.

To help you choose from the hundreds of heads out there, in the box above are my choices for the top 10 (in random order). Consider each one's attributes and choose the head that best fits your hunting style and quarry.

get real - video archery

Practice is a lot like dental flossing: Nobody doubts the benefits, but who's got the time for a consistent routine? That's about to change, at least on the archery scene.

If sporting clays is like golf with a shotgun, 3-D archery ranges are Pebble Beach with a bow and arrow. Life-size three-dimensional foam animal targets are arranged throughout a natural setting and shots are taken at unmarked distances. Grizzlies, elk, turkeys, muleys, whitetails - you name it.

It's primarily a sport for practice, but competitions are held at regional and national levels. And its popularity is huge: At the two major national competitions last year, a total of 11,000 shooters registered. According to the organizer, International Bowhunting Organization (I.B.O.), these figures could double in 1994.

The second big development comes on the cutting edge of technology. The interactive-video generation is here, friends, and bowhunting happily has its roots down. Instead of shooting at stationary, three-dimensional targets, archers take aim at moving, full-color game on screen. Shooters must decide precisely when and where to shoot during each sequence, taking into account the animal's body angle, movement, obstructions and so on.

The Dart Target System is the current leader. You stand at one end of a dark tunnel, 20 yards from projected images. When your arrow, equipped with a special blunt, strikes the screen its location is fed to a computer via infrared sensor. The animal image freezes, the heart and. lungs kill zone is projected (in correct relation to the animal's body angle) and the hit appears as a dot. A heart shot equals 10 points, lungs five.

A similar format, Interactive Target Systems (ITS), offers three laser disc systems. Up to five archers can shoot in rotation, and some models track arrow speed and sport a "wind" feature that requires some compensation.

Another version, called Archery Visions, displays animals on a regular white target butt so that shooters can use their usual field tips or broadheads. Arrows stick into a target that shows vital zones, which are invisible while the animal image is projected. Although this system is a little less high-tech, shooters like it because they can use their standard equipment without additional tuning or compensation in shooting style.

Target practice will never be the same. Fewer bowhunters are making excuses for not practicing and more are complaining about not being able to practice enough. I guess dental flossing will just have to wait.

Source Citation

Adams, Chuck, et al. "Beyond basics bowhunting." Outdoor Life Aug. 1994: 56+. General OneFile. Web. 14 Feb. 2011.

Document URL

http://find.galegroup.com/gps/infomark.do?&contentSet=IAC-Documents&type=retrieve&tabID=T003&prodId=IPS&docId=A15587275&source=gale&srcprod=ITOF&userGroupName=22054_acld&version=1.0

Gale Document Number:A15587275

No comments:

Post a Comment